The origin of kaniwa, also commercialized as "baby quinoa" and locally known as cañihua or qañiwua (pronounced kah-nyee-wah), among many other names, can be traced to the southern Andes of Peru and Bolivia. Due to its great nutritional value, its ability to thrive at very high altitudes, and its resistance to very low temperatures, kaniwa has been a staple in the diet of Andean people for millennia. Its benefits are just starting to be recognized around the world.

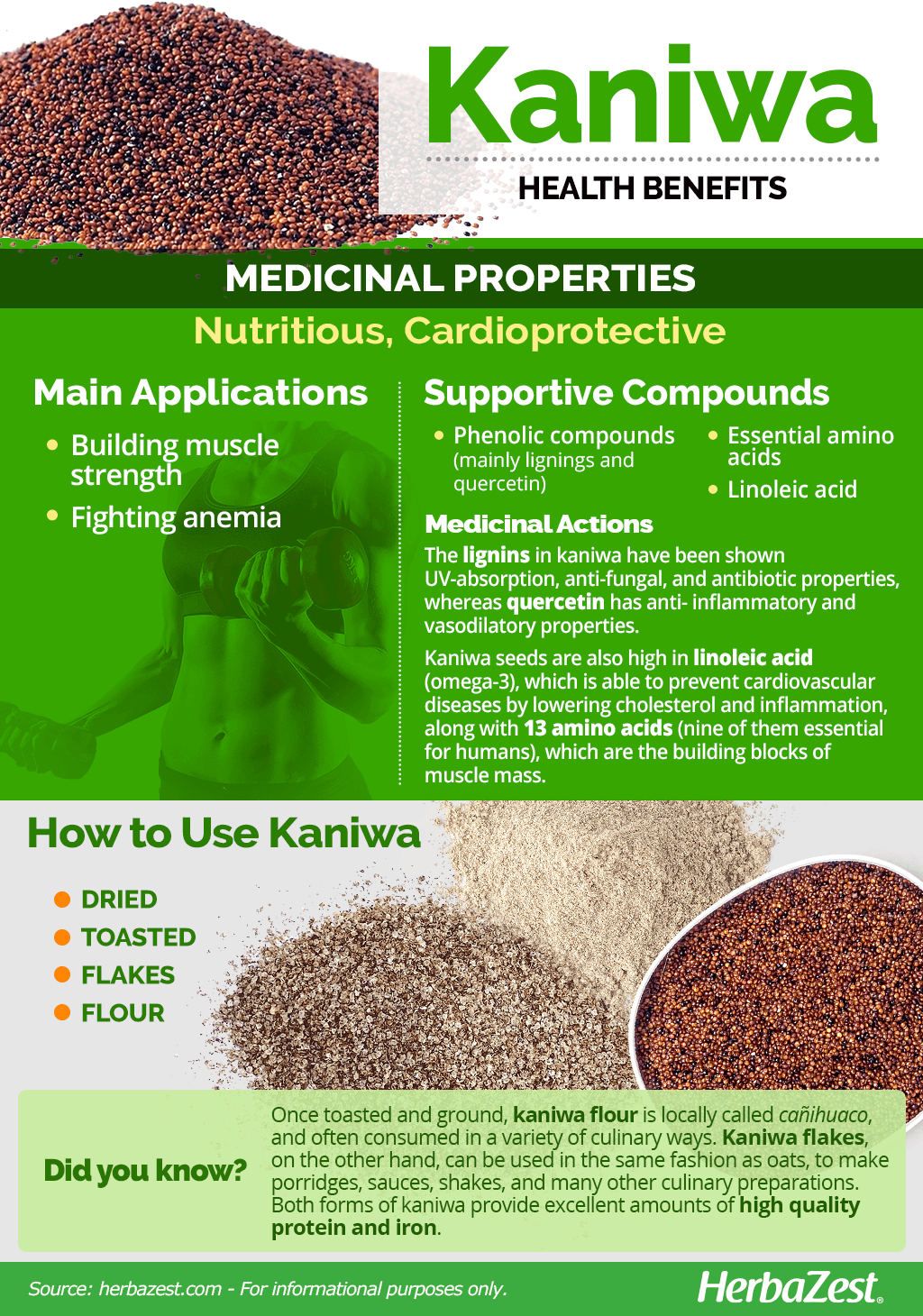

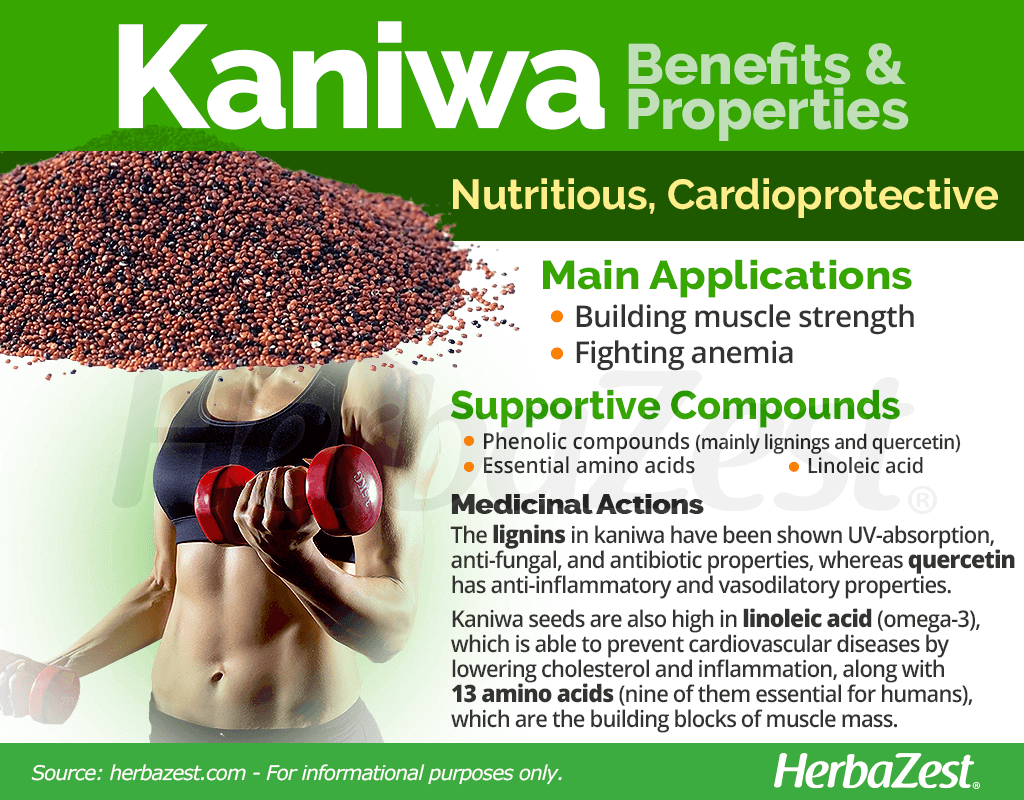

Kaniwa Medicinal Properties

- Medicinal action Cardioprotective, Nutritious

- Key constituents Phenolic compounds (mainly lignings and quercetin), essential amino acids, linoleic acid

- Ways to use Food

- Medicinal rating (3) Reasonably useful plant

- Safety ranking Safe

Health Benefits of Kaniwa

While most kaniwa benefits hail from its nutritional content, it is also rich in antioxidants, which are thought to be responsible for some of its medicinal properties. Although research about this Andean native pseudocereal is scarce, it is known to help with:

Building muscle strength. The concentration of essential amino acids in kaniwa grains helps to build and maintain a healthy muscle mass, which makes it a great supplement for people following vegan or vegetarian diets.

Fighting anemia. Being rich in iron, kaniwa has been a great ally in fighting and preventing anemia among Andean populations for thousands of years.

Additional kaniwa benefits, suggested by traditional uses and preliminary studies, are:

Aiding digestion. Kaniwa grains are particularly rich in soluble fiber, which improves digestion and promotes gastrointestinal health. It is ideal for people with gastritis and ulcers since it can be easily incorporated in a bland diet.

Enhancing metabolic functions. Similarly to quinoa, the rich antioxidant content of kaniwa is thought to help treat and prevent diabetes by controlling cholesterol, hypertension, and blood sugar, thus reducing the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

TRADITIONALLY, KANIWA HAS ALSO BEEN USED FOR COUNTERACTING ALTITUDE SICKNESS AND TREATING DYSENTERY.

How It Works

Although scientific research on kaniwa is still scarce, preliminary studies have suggested that this Andean pseudocereal is rich in phenolic compounds, well-known for their antioxidant properties. Lignins in particular been shown to possess antioxidant, UV-absorption, anti-fungal, and antibiotic properties.1

On the other hand, kaniwa seeds are rich in quercetin aglycone, a highly bioavailable form of quercetin with anti-inflammatory and vasodilatory properties.

Kaniwa grains also contain high amounts of linoleic acid (omega-6), an essential fatty acid with the ability of lowering cholesterol levels and inflammation, thus contributing to preventing cardiovascular diseases.

Additionally, kaniwa contains 13 amino acids (nine of them essential for humans) which are the building blocks of protein, necessary for creating and maintaining muscle mass.

KANIWA IS GLUTEN-FREE, WHICH MAKES IT SAFE FOR CONSUMPTION BY PEOPLE WITH CELIAC DISEASE AND GLUTEN SENSITIVITY.

Other herbs with cardioprotective, cholesterol-lowering benefits are avocado, flax, oats, and olive.

Kaniwa Side Effects

The limited research on kaniwa makes it difficult to determine their safety in all instances; however, this close relative of quinoa doesn't contain saponins, making it easier to process and consume.

Despite the lack of scientific data, a long-term consumption of kaniwa in the extreme highlands of Peru and Bolivia vouch for its great nutritional value and safety for direct consumption.

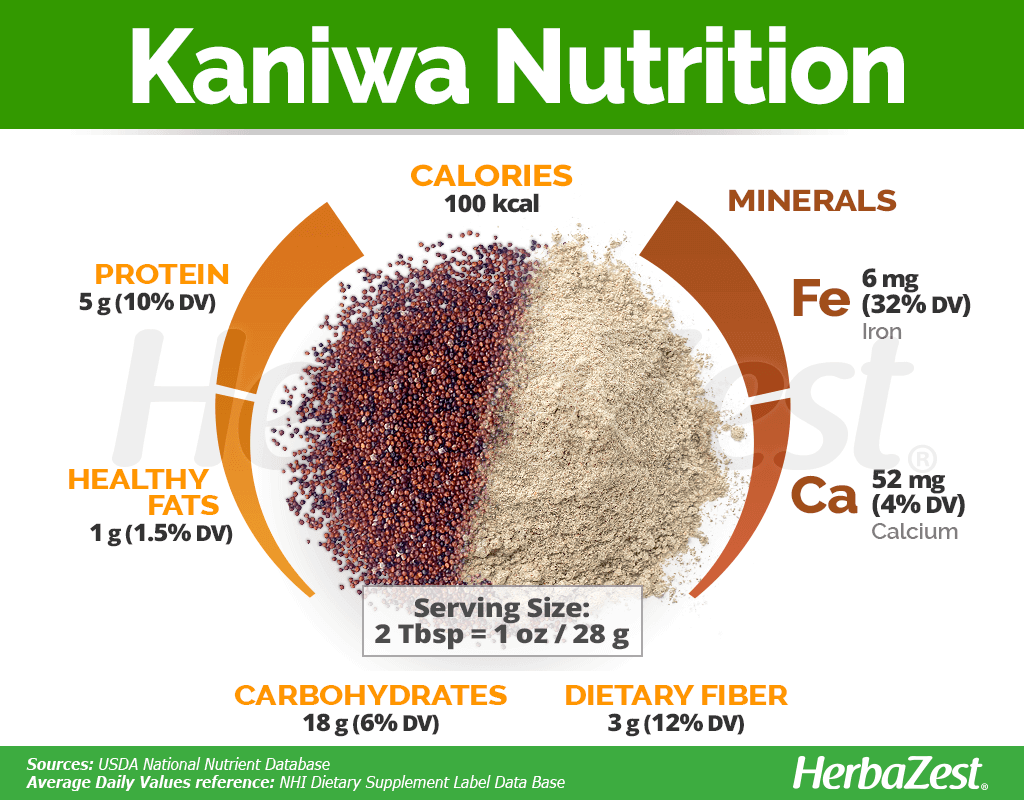

Kaniwa Nutrition

Kaniwa seeds are particularly rich in soluble fiber and high-quality protein, even surpassing its more famous relative, quinoa. This is particularly significant for the mostly starchy diets of the high-altitude Andean communities, where not even quinoa can be grown.

Kaniwa is also a powerhouse of minerals when compared to other Andean pseudocereals considered as "superfoods," such as quinoa and amaranth. Kaniwa provides excellent levels of iron as well as good amounts of calcium, both of which are highly bioavailable, meaning they are easily absorbed by the body.2

Due to its great nutritional value, elderly people and those with iron deficiency can benefit from consuming kaniwa.

ONE OUNCE (28.35G) OF KANIWA PROVIDES 100 CALORIES AS WELL AS 32 AND 10% OF THE DAILY VALUE FOR IRON AND PROTEIN.

Kaniwa makes part of an exclusive list of highly nutritious and medicinal crops from South America, including amaranth, maca, mashua, quinoa, and sacha inchi.

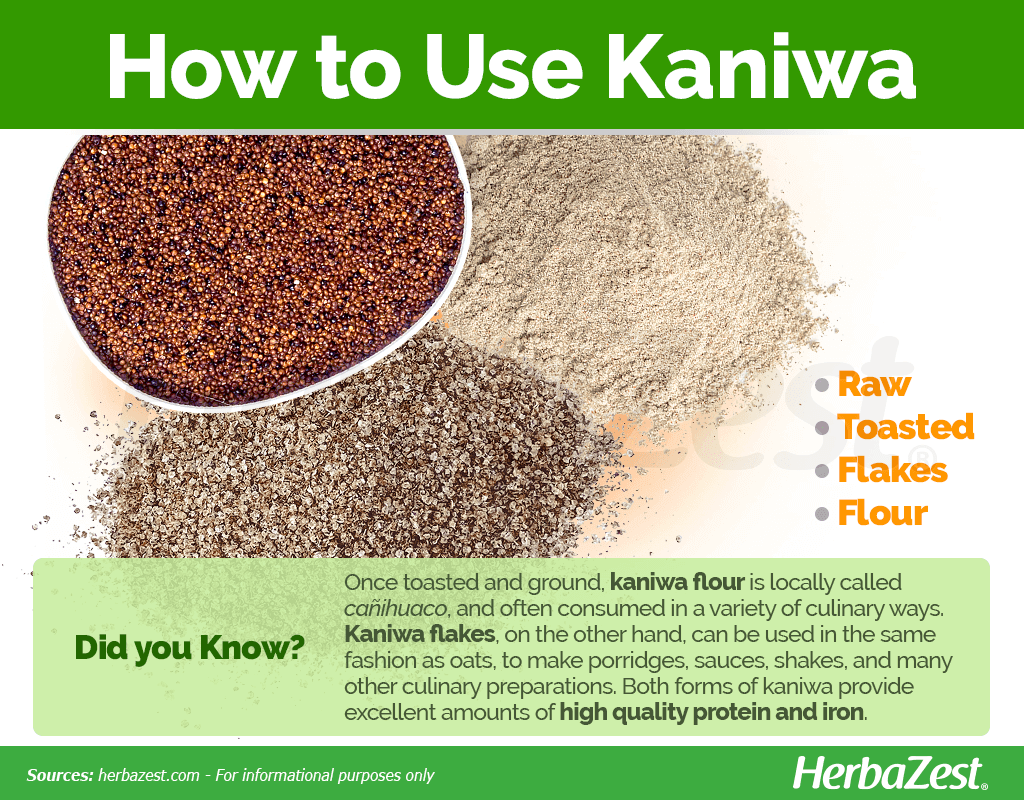

How to Consume Kaniwa

- Edible parts Seed

- Edible uses Protein

Young kaniwa leaves, which contain as much as 30% of protein, are easy to digest and locally used as a fodder.3

The kaniwa grain or seed has been traditionally consumed roasted, either whole or ground. This method gives the seeds a pleasant, nutty flavor, which is used in a wide variety of culinary preparations. However, the whole dried kaniwa grain can also be consumed cooked in the same fashion as quinoa.

Natural Forms

Dried. The tiny dried seeds of kaniwa are used for a variety of cooked dishes in a similar way as quinoa.

Roasted. This is the most traditional way of consuming the kaniwa grain in order to reap its health benefits and nutritional value.

Flakes. Kaniwa flakes can be used in the same fashion as oats to make porridges, sauces, baked goods, smoothies, and many other culinary preparations.

Flour. Once roasted and ground, the kaniwua grain or seed is transformed into kaniwa flour, which is locally called cañihuaco and often consumed in a variety of culinary ways.

Growing

- Life cycle Annual

- Harvested parts Seeds, Leaves

- Light requirements Full sun

- Growing habitat Andean region

The kaniwa plant (Chenopodium pallidicaule) is very resistant to the harsh climate in the extreme highlands of Peru and Bolivia, at altitudes between 12,500 ft. and 14,100 ft. (3,800 and 4,300 m). Perfectly adapted to the inhospitable Andean environment, the seeds can germinate on the plant itself if there is sufficient humidity.

Partly wild, kaniwa plants show spontaneous loss and dispersal of seeds, which can remain in the soil where kaniwa has been grown for several years.3

Additional Information

- Other uses Animal feed, Dye, Repellent

Plant Biology

The kaniwa plant is an annual broadleaf herb that can grow from 10 to 28 inches (25 - 70 cm) tall. When ready to harvest, kaniwa leaves and stem turn yellow, pink, orange, red, or purple. Its inflorescences are covered by the leaves, and its flowers, which can be hermaphrodite, pistillate, or sterile, are small and have no petals. The seed is from 0.02 to 0.6 inches (0.5 to 1.5 mm) in diameter and can be brown or black.3

Classification

Kaniwa is consumed as a grain; however, this species is technically a seed, often recognized as a pseudocereal. “True cereals,” like maize, wheat, oats, and rice, are tall grasses, whereas pseudocerals, such as quinoa, kaniwa, and amaranth, are broadleaf plants.

The kaniwa plant, or Chenopodium pallidicaule, a close relative of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), is a member of the Amaranthaceae family, which contains 2,500 species spread out over 180 genera. This family includes many flowering plants, and though it is a widespread family, most of its members are found in tropical areas. It contains other well-known and economically-important herbs, such as amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus), spinach (Spinacia oleracea), and beetroot (Beta vulgaris).

Varieties of Kaniwa

The pattern of the kaniwa plant branches depends on the type: Saigua exhibits a few secondary branches, whereas Lasta is more densely branched. Each of these types is further classified by the black or brown color of the seed.

Historical information

The kaniwa plant is native to the South American Andes, mainly the highlands of Bolivia and Peru. It was first discovered thousands of years ago at altitudes between 12,500 ft. and 14,100 ft. (3,800 and 4,300 m), in an inhospitable region where not even quinoa thrives due to the extremely cold temperatures.

The Tiahuanaco civilization partially domesticated kaniwa for human and animal consumption, and, even though the archeological evidence is scarce, it is thought that this pseudocereal was key to human development at the shores of Lake Titicaca, the highest navigable water surface on the planet.

The amazing nutritional value of kaniwa has been recently discovered by the Western World, and even when countries like Finland are attempting to cultivate it, its farming remains mainly restricted to its native Andean lands.

Economic Data

Kaniwa, often commercialized under the name is "baby quinoa," has experienced a rise in consumption during the last years; however, is not yet as popular or widely distributed as quinoa. Currently, it is still a semi-domesticated crop, mainly cultivated for local consumption among the Andean communities. Another reason for kaniwa's limited trade is the small size of its seeds, which requires a large number of workers for harvesting and makes the processing more challenging.

Although kaniwa is a hardy crop due to its particular requirements of temperature and humidity, it has little potential for being commercially cultivated in other latitudes, such as North America and Europe.

Meanwhile, kaniwa is quickly becoming popular for its great nutritional benefits, similar and even superior to quinoa in some aspects.3

Other Uses

Repellent. The ashes of kaniwa stems are traditionally used to ward off insects and prevent spider bites.

Fodder. Once kaniwa seeds or grains are harvested, the dried upper parts of the plant are used to feed farm animals.

Dye. The kaniwa plant can be used to extract gold and green dyes.

Sources

- Food and Nutrition Journal, Bioavailability of Quercetin, 2016

- Food Reviews International, Nutritional Value and Use of the Andean Crops Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and Kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule), 2006

- Global Facilitation Unit for Underutilized Species, Canihua - Chenopodium pallidicaule

- International Journal of Molecular Sciences, Lignins: Biosynthesis and Biological Functions in Plants, 2018

- Journal of Medicinal Foods, Evaluation of indigenous grains from the Peruvian Andean region for antidiabetes and antihypertension potential using in vitro methods, 2009

- Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation, pp. 129-138

- Whole Grains Council, Kañiwua

Footnotes:

- Boeriu, C. et al. (2004). Characterisation of structure-dependent functional properties of lignin with infrared spectroscopy. Retrieved January 10, 2020 from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0926669004000731

- Hernández Bermejo, J.E. and León, J. (1994). Neglected Crops: 1492 from a Different Perspective. Retrieved January 10, 2020 from http://www.fao.org/3/t0646e/t0646e.pdf

- National Research Council. (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press